Download Full Unedited Text Of Mein Kampf

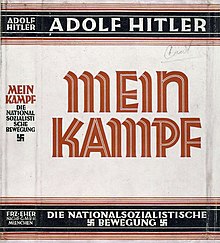

Dust jacket of 1926–1928 edition | |

| Author | Adolf Hitler |

|---|---|

| State | German Reich |

| Linguistic communication | High german |

| Bailiwick | Autobiography Political manifesto Political philosophy |

| Publisher | Franz Eher Nachfolger GmbH |

| Publication appointment | 18 July 1925 |

| Published in English | 13 October 1933 (abridged) 1939 (full) |

| Media blazon | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 720 |

| ISBN | 978-0395951057 (1998) trans. by Ralph Manheim |

| Dewey Decimal | 943.086092 |

| LC Course | DD247.H5 |

| Followed past | Zweites Buch |

Mein Kampf (High german: [maɪn ˈkampf]; My Struggle or My Battle) is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Frg. Book 1 of Mein Kampf was published in 1925 and Volume 2 in 1926.[1] The book was edited first by Emil Maurice, then past Hitler's deputy Rudolf Hess.[ii] [3]

Hitler began Mein Kampf while imprisoned following his failed insurrection in Munich in November 1923 and a trial in February 1924 for high treason, in which he received the very light sentence of five years. Although he received many visitors initially, he soon devoted himself entirely to the volume. Every bit he continued, he realized that it would take to exist a two-book work, with the offset volume scheduled for release in early 1925. The governor of Landsberg noted at the time that "he [Hitler] hopes the book volition see many editions, thus enabling him to fulfill his financial obligations and to defray the expenses incurred at the fourth dimension of his trial."[4] [5] Afterward ho-hum initial sales, the volume became a bestseller in Federal republic of germany following Hitler's rise to ability in 1933.[6]

After Hitler's decease, copyright of Mein Kampf passed to the land government of Bavaria, which refused to allow any copying or printing of the volume in Germany. In 2016, post-obit the expiration of the copyright held by the Bavarian state regime, Mein Kampf was republished in Germany for the first fourth dimension since 1945, which prompted public fence and divided reactions from Jewish groups. A team of scholars from the Constitute for Gimmicky History in Munich published a German-language two-volume almost 2,000-page edition annotated with about 3,500 notes. This was followed in 2021 by a 1,000-page French edition based on the German annotated version, with most twice equally much commentary as text.

Title

Hitler originally wanted to call his forthcoming volume Viereinhalb Jahre (des Kampfes) gegen Lüge, Dummheit und Feigheit (Four and a One-half Years [of Struggle] Confronting Lies, Stupidity and Cowardice).[7] Max Amann, caput of the Franz Eher Verlag and Hitler'south publisher, is said to take suggested[viii] the much shorter "Mein Kampf" ("My Struggle").

Contents

The organisation of chapters is every bit follows:

- Volume 1: A Reckoning

- Chapter ane: In the Business firm of My Parents

- Affiliate 2: Years of Report and Suffering in Vienna

- Chapter 3: Full general Political Considerations Based on My Vienna Period

- Affiliate 4: Munich

- Chapter 5: The World War

- Chapter 6: War Propaganda

- Chapter vii: The Revolution

- Chapter 8: The Beginning of My Political Action

- Chapter 9: The "German Workers' Party"

- Chapter ten: Causes of the Collapse

- Affiliate 11: Nation and Race

- Chapter 12: The First Menstruation of Development of the National Socialist German language Workers' Party

- Volume Two: The National Socialist Movement

- Affiliate 1: Philosophy and Party

- Affiliate 2: The State

- Chapter 3: Subjects and Citizens

- Chapter 4: Personality and the Conception of the Völkisch State

- Chapter 5: Philosophy and System

- Chapter 6: The Struggle of the Early on Period – the Significance of the Spoken Word

- Affiliate 7: The Struggle with the Cherry-red Front

- Chapter 8: The Strong Man Is Mightiest Alone

- Chapter ix: Bones Ideas Regarding the Pregnant and Organisation of the Sturmabteilung

- Chapter ten: Federalism equally a Mask

- Chapter eleven: Propaganda and Organization

- Chapter 12: The Trade-Union Question

- Chapter 13: German Alliance Policy Later on the War

- Chapter xiv: Eastern Orientation or Eastern Policy

- Affiliate fifteen: The Right of Emergency Defense force

- Conclusion

- Alphabetize

Analysis

In Mein Kampf , Hitler used the master thesis of "the Jewish peril", which posits a Jewish conspiracy to gain world leadership.[ix] The narrative describes the process by which he became increasingly antisemitic and militaristic, peculiarly during his years in Vienna. He speaks of not having met a Jew until he arrived in Vienna, and that at commencement his mental attitude was liberal and tolerant. When he first encountered the antisemitic press, he says, he dismissed information technology every bit unworthy of serious consideration. Later he accustomed the same antisemitic views, which became crucial to his program of national reconstruction of Germany.

Mein Kampf has besides been studied every bit a piece of work on political theory. For example, Hitler announces his hatred of what he believed to be the earth'due south two evils: Communism and Judaism.

In the book Hitler blamed Federal republic of germany'southward chief woes on the parliament of the Weimar Republic, the Jews, and Social Democrats, besides as Marxists, though he believed that Marxists, Social Democrats, and the parliament were all working for Jewish interests.[ten] He announced that he wanted to completely destroy the parliamentary organisation, believing it to be decadent in principle, as those who reach power are inherent opportunists.

Antisemitism

While historians dispute the exact date Hitler decided to exterminate the Jewish people, few place the decision before the mid-1930s.[11] First published in 1925, Mein Kampf shows Hitler's personal grievances and his ambitions for creating a New Order. Hitler also wrote that The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a fabricated text which purported to betrayal the Jewish plot to command the earth,[12] was an authentic document. This later became a part of the Nazi propaganda effort to justify persecution and annihilation of the Jews.[13] [14]

The historian Ian Kershaw points out that several passages in Mein Kampf are undeniably of a genocidal nature.[xv] Hitler wrote "the nationalization of our masses will succeed just when, bated from all the positive struggle for the soul of our people, their international poisoners are exterminated",[16] and he suggested that, "If at the offset of the war and during the war twelve or fifteen thousand of these Hebrew corrupters of the nation had been subjected to poison gas, such as had to be endured in the field past hundreds of thousands of our very best High german workers of all classes and professions, and then the sacrifice of millions at the forepart would not have been in vain."[17]

The racial laws to which Hitler referred resonate direct with his ideas in Mein Kampf . In the showtime edition, Hitler stated that the destruction of the weak and sick is far more than humane than their protection. Apart from this allusion to humane treatment, Hitler saw a purpose in destroying "the weak" in society to provide the proper infinite and purity for the "stiff".[18]

Lebensraum ("living infinite")

In the chapter "Eastern Orientation or Eastern Policy", Hitler argued that the Germans needed Lebensraum in the Due east, a "historic destiny" that would properly nurture the High german people.[19] Hitler believed that "the organization of a Russian country germination was not the result of the political abilities of the Slavs in Russian federation, but only a wonderful example of the country-forming efficacy of the High german element in an junior race."[xx]

In Mein Kampf Hitler openly stated the time to come German expansion in the Due east, foreshadowing Generalplan Ost:

And and so we National Socialists consciously depict a line beneath the foreign policy tendency of our pre-War period. We have upwards where we broke off half dozen hundred years ago. Nosotros stop the endless High german movement to the southward and west, and turn our gaze toward the country in the due east. At long terminal we break off the colonial and commercial policy of the pre-War period and shift to the soil policy of the futurity. If nosotros speak of soil in Europe today, we tin can primarily take in heed just Russian federation and her vassal edge states.[21]

Popularity

Standard arabic edition of Mein Kampf

Although Hitler originally wrote Mein Kampf more often than not for the followers of National Socialism, it grew in popularity later on he rose to power. (Ii other books written past political party members, Gottfried Feder's Breaking The Interest Slavery and Alfred Rosenberg's The Myth of the Twentieth Century, have since lapsed into comparative literary obscurity.)[22] Hitler had made near ane.2 meg Reichsmarks from the income of the volume past 1933 (equivalent to €5,139,482 in 2017), when the average annual income of a teacher was nearly 4,800 Marks (equivalent to €20,558 in 2017).[22] [23] He accumulated a tax debt of 405,500 Reichsmark (very roughly in 2015 1.i million GBP, 1.4 1000000 EUR, 1.5 meg USD) from the auction of nearly 240,000 copies before he became chancellor in 1933 (at which time his debt was waived).[22] [23]

Hitler began to distance himself from the book after condign chancellor of Frg in 1933. He dismissed it every bit "fantasies behind confined" that were little more than a series of articles for the Völkischer Beobachter , and later told Hans Frank that "If I had had any thought in 1924 that I would have become Reich chancellor, I never would have written the book."[24] Nevertheless, Mein Kampf was a bestseller in Germany during the 1930s.[25] During Hitler'south years in power, the book was in loftier demand in libraries and frequently reviewed and quoted in other publications. It was given free to every newlywed couple and every soldier fighting at the front.[22] By 1939 it had sold five.ii million copies in eleven languages.[26] By the end of the war, about 10 million copies of the book had been sold or distributed in Frg.[ commendation needed ]

Contemporary observations

Mein Kampf , in essence, lays out the ideological plan Hitler established for the German revolution, by identifying the Jews and "Bolsheviks" as racially and ideologically inferior and threatening, and "Aryans" and National Socialists every bit racially superior and politically progressive. Hitler's revolutionary goals included expulsion of the Jews from Greater Germany and the unification of German peoples into one Greater Frg. Hitler desired to restore German lands to their greatest historical extent, real or imagined.

Due to its racist content and the historical result of Nazism upon Europe during World War Ii and the Holocaust, it is considered a highly controversial book. Criticism has not come solely from opponents of Nazism. Italian Fascist dictator and Nazi ally Benito Mussolini was also critical of the book, saying that it was "a boring tome that I have never been able to read" and remarking that Hitler'southward beliefs, as expressed in the volume, were "footling more than than commonplace clichés".[27]

The German language journalist Konrad Heiden, an early critic of the Nazi Political party, observed that the content of Mein Kampf is essentially a political argument with other members of the Nazi Party who had appeared to be Hitler's friends, just whom he was actually denouncing in the book's content – sometimes past non fifty-fifty including references to them.[ citation needed ]

The American literary theorist and philosopher Kenneth Burke wrote a 1939 rhetorical analysis of the work, The Rhetoric of Hitler'southward "Battle", which revealed an underlying message of aggressive intent.[28]

The American journalist John Gunther said in 1940 that compared to the autobiographies such as Leon Trotsky'southward My Life or Henry Adams'south The Instruction of Henry Adams, Mein Kampf was "vapid, vain, rhetorical, diffuse, prolix." However, he added that "it is a powerful and moving book, the product of peachy passionate feeling". He suggested that the book wearied curious German readers, but its "ceaseless repetition of the argument, left impregnably in their minds, fecund and germinating".[29]

In March 1940, British writer George Orwell reviewed a then-recently published uncensored translation of Mein Kampf for The New English Weekly. Orwell suggested that the strength of Hitler'due south personality shone through the often "clumsy" writing, capturing the magnetic allure of Hitler for many Germans. In essence, Orwell notes, Hitler offers only visions of endless struggle and conflict in the cosmos of "a horrible brainless empire" that "stretch[es] to Afghanistan or thereabouts". He wrote, "Whereas Socialism, and even commercialism in a more grudging way, have said to people 'I offer you a good time,' Hitler has said to them, 'I offer y'all struggle, danger, and expiry,' and as a result a whole nation flings itself at his feet." Orwell's review was written in the aftermath of the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, when Hitler fabricated peace with USSR after more than a decade of vitriolic rhetoric and threats betwixt the two nations; with the pact in place, Orwell believed, England was now facing a hazard of Nazi attack and the United kingdom must not underestimate the entreatment of Hitler's ideas.[30]

In his 1943 book The Menace of the Herd, Austrian scholar Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn[31] described Hitler'due south ideas in Mein Kampf and elsewhere as "a veritable reductio ad absurdum of 'progressive' thought"[32] and betraying "a curious lack of original thought" that shows Hitler offered no innovative or original ideas merely was merely "a virtuoso of commonplaces which he may or may non repeat in the guise of a 'new discovery.'"[33] Hitler'due south stated aim, Kuehnelt-Leddihn writes, is to quash individualism in furtherance of political goals:

When Hitler and Mussolini set on the "western democracies" they insinuate that their "commonwealth" is not genuine. National Socialism envisages abolishing the deviation in wealth, education, intellect, gustatory modality, philosophy, and habits by a leveling process which necessitates in plow a total control over the kid and the adolescent. Every personal attitude will be branded—subsequently communist pattern—as "bourgeois," and this in spite of the fact that the bourgeois is the representative of the most herdist grade in the world, and that National Socialism is a basically conservative move. In Mein Kampf , Hitler repeatedly speaks of the "masses" and the "herd" referring to the people. The German people should probably, in his view, remain a mass of identical "individuals" in an enormous sand heap or ant heap, identical fifty-fifty to the color of their shirts, the garment nearest to the body.[34]

In his The Second World War, published in several volumes in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Winston Churchill wrote that he felt that after Hitler's rise to power, no other volume than Mein Kampf deserved more intensive scrutiny.[35]

Later assay

The critic George Steiner has suggested that Mein Kampf can exist seen as one of several books that resulted from the crisis of High german culture post-obit Deutschland's defeat in Earth War I, comparable in this respect to the philosopher Ernst Bloch'south The Spirit of Utopia (1918), the historian Oswald Spengler'southward The Decline of the West (1918), the theologian Franz Rosenzweig'due south The Star of Redemption (1921), the theologian Karl Barth'due south The Epistle to the Romans (1922), and the philosopher Martin Heidegger's Being and Time (1927).[36]

On translation

A number of translators have commented on the poor quality of Hitler's use of language in writing Mein Kampf. Olivier Mannoni, who translated the 2021 French critical edition, said about the original German text that it was "An incoherent soup, i could become one-half-mad translating information technology," and said that previous translations had corrected the language, giving the false impression that Hitler was a "cultured human being" with "coherent and grammatically correct reasoning". He added "To me, making this text elegant is a crime."[37] Mannoni'southward comments are like to those made by Ralph Manheim, who did the offset English language-linguistic communication translation in 1943. Mannheim wrote in the foreword to the edition "Where Hitler's formulations challenge the reader's credulity I have quoted the German language original in the notes." This evaluation of the awfulness of Hitler's prose and his inability to express his opinions coherently was shared by William S. Schlamm, who reviewed Manheim'due south translation in The New York Times, writing that "in that location was not the faintest similarity to a thought and barely a trace of language."[38]

German publication history

While Hitler was in power (1933–1945), Mein Kampf came to exist available in three common editions. The first, the Volksausgabe or People's Edition, featured the original cover on the dust jacket and was navy blueish underneath with a gold swastika eagle embossed on the cover. The Hochzeitsausgabe , or Wedding Edition, in a slipcase with the seal of the province embossed in gold onto a parchment-like encompass was given free to marrying couples. In 1940, the Tornister-Ausgabe , or Knapsack Edition, was released. This edition was a compact, but entire, version in a red cover and was released by the post office, available to exist sent to loved ones fighting at the front. These three editions combined both volumes into the same book.

A special edition was published in 1939 in award of Hitler's 50th birthday. This edition was known as the Jubiläumsausgabe , or Ceremony Issue. Information technology came in both dark blueish and bright red boards with a gold sword on the embrace. This piece of work contained both volumes one and two. It was considered a deluxe version, relative to the smaller and more than common Volksausgabe .

The volume could also be purchased every bit a two-volume fix during Hitler'south rule, and was bachelor in soft encompass and hardcover. The soft encompass edition independent the original cover (as pictured at the top of this article). The hardcover edition had a leather spine with cloth-covered boards. The cover and spine contained an image of iii brown oak leaves.

2016 disquisitional edition

Afterward Hitler's death, the copyright passed to the authorities of Bavaria, which refused to allow it to be republished. The copyright ran out on December 31, 2015.

On three Feb 2010, the Constitute of Contemporary History (IfZ) in Munich announced plans to republish an annotated version of the text, for educational purposes in schools and universities, in 2015. The book had last been published in Federal republic of germany in 1945.[39] The IfZ argued that a republication was necessary to get an authoritative annotated edition past the time the copyright ran out, which might open the mode for neo-Nazi groups to publish their ain versions.[40] The Bavarian Finance Ministry opposed the plan, citing respect for victims of the Holocaust. Information technology stated that permits for reprints would not be issued, at abode or abroad. This would too apply to a new annotated edition. There was disagreement about the issue of whether the republished book might be banned equally Nazi propaganda. The Bavarian government emphasized that fifty-fifty after expiration of the copyright, "the dissemination of Nazi ideologies will remain prohibited in Deutschland and is punishable nether the penal code".[41] Still, the Bavarian Science Minister Wolfgang Heubisch supported a critical edition, stating in 2010 that, "Once Bavaria's copyright expires, in that location is the danger of charlatans and neo-Nazis appropriating this infamous book for themselves".[forty]

On 12 Dec 2013 the Bavarian government cancelled its financial back up for an annotated edition. IfZ, which was preparing the translation, announced that it intended to proceed with publication after the copyright expired.[42] The IfZ scheduled an edition of Mein Kampf for release in 2016.[43]

Richard Verber, vice-president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, stated in 2015 that the board trusted the academic and educational value of republishing. "We would, of class, exist very wary of any endeavour to glorify Hitler or to belittle the Holocaust in whatsoever way", Verber declared to The Observer. "Simply this is not that. I do understand how some Jewish groups could be upset and nervous, merely it seems it is being washed from a historical point of view and to put it in context".[44]

The annotated edition of Mein Kampf was published in Germany in January 2016 and sold out within hours on Amazon's German language site. The two-book edition included almost iii,500 notes, and was almost ii,000 pages long.[45]

The volume'south publication led to public debate in Germany, and divided reactions from Jewish groups, with some supporting, and others opposing, the conclusion to publish.[25] German language officials had previously said they would limit public access to the text amid fears that its republication could stir neo-Nazi sentiment.[46] Some bookstores stated that they would not stock the volume. Dussmann, a Berlin bookstore, stated that one copy was bachelor on the shelves in the history department, but that it would not be advertised and more copies would exist available only on guild.[47] By January 2017, the German annotated edition had sold over 85,000 copies.[48]

English translations

Always since the early on 1930s, the history of Adolf Hitler's Mein Kampf in English has been complicated and has been the occasion for controversy.[49] [fifty] No fewer than four full translations were completed earlier 1945, also every bit a number of extracts in newspapers, pamphlets, authorities documents and unpublished typescripts. Not all of these had official approval from his publishers, Eher Verlag. Since the war, the 1943 Ralph Manheim translation has been the most pop published translation, though other versions have connected to circulate.

Current availability

At the time of his suicide, Hitler'southward official place of residence was in Munich, which led to his entire estate, including all rights to Mein Kampf , changing to the ownership of the state of Bavaria. The regime of Bavaria, in agreement with the federal regime of Germany, refused to allow whatever copying or press of the book in Frg. Information technology likewise opposed copying and printing in other countries, but with less success. As per German copyright constabulary, the entire text entered the public domain on i January 2016, upon the expiration of the calendar yr 70 years later on the author's death.[51]

Owning and buying the volume in Deutschland is not an offence. Trading in old copies is lawful likewise, unless it is done in such a fashion as to "promote hatred or war." In particular, the unmodified edition is not covered by §86 StGB that forbids dissemination of ways of propaganda of unconstitutional organizations, since it is a "pre-constitutional work" and every bit such cannot be opposed to the free and democratic basic gild, according to a 1979 decision of the Federal Court of Justice of Germany.[52] Most German libraries acquit heavily commented and excerpted versions of Mein Kampf . In 2008, Stephan Kramer, secretarial assistant-general of the Central Council of Jews in Deutschland, non only recommended lifting the ban, but volunteered the help of his organization in editing and annotating the text, proverb that it is time for the book to be made available to all online.[53]

A variety of restrictions or special circumstances apply in other countries.

French republic

In 1934, the French government unofficially sponsored the publication of an unauthorized translation. It was meant equally a warning and included a critical introduction by Marshal Lyautey ("Every Frenchman must read this book"). Information technology was published by far-right publisher Fernand Sorlot in an agreement with the activists of LICRA who bought 5000 copies to exist offered to "influential people"; however, most of them treated the book as a casual gift and did non read it.[54] The Nazi regime unsuccessfully tried to have it forbidden. Hitler, as the writer, and Eher-Verlag, his German publisher, had to sue for copyright infringement in the Commercial Court of France. Hitler'due south lawsuit succeeded in having all copies seized, the print broken up, and having an injunction against booksellers offer any copies. Even so, a large quantity of books had already been shipped and stayed available undercover by Sorlot.[55]

In 1938, Hitler licensed for France an authorized edition by Fayard, translated by François Dauture and Georges Blond, lacking the threatening tone confronting France of the original. The French edition was 347 pages long, while the original championship was 687 pages, and it was titled Ma doctrine ("My doctrine").[56]

After the war, Fernand Sorlot re-edited, re-issued, and continued to sell the work, without permission from the land of Bavaria, to which the author's rights had defaulted.

In the 1970s, the ascent of the extreme right in France forth with the growing of Holocaust deprival works, placed the Mein Kampf under judicial watch and in 1978, LICRA entered a complaint in the courts against the publisher for inciting antisemitism. Sorlot received a "substantial fine" just the court also granted him the right to continue publishing the work, provided certain warnings and qualifiers accompany the text.[55]

On 1 January 2016, 70 years afterwards the writer's death, Mein Kampf entered the public domain in France.[55]

A new edition was published in 2017 by Fayard, now office of the Groupe Hachette, with a critical introduction, just every bit the edition published in 2018 in Frg by the Institut für Zeitgeschichte , the Institute of Contemporary History based in Munich.[55]

In 2021, a 1,000 folio disquisitional edition, based on the German edition of 2016, was published in France. Titled Historiciser le mal: Une édition critique de Mein Kampf ("Historicizing Evil: A Critical Edition of Mein Kampf"), with almost twice as much commentary equally text, it was edited by Florent Brayard and Andraes Wirsching, translated by Olivier Mannoni, and published by Fayard. The impress run was deliberately kept small at 10,000 bachelor but by special order, with copies set aside for public libraries. Proceeds from the auction of the edition are earmarked for the Auschwitz-Birkenau Foundation. Some critics who had objected in accelerate to the edition's publication had fewer objections upon publication. Ane historian noted that there were and so many annotations that Hitler'due south text had become "secondary."[37]

India

Since its first publication in India in 1928, Mein Kampf has gone through hundreds of editions and sold over 100,000 copies.[57] [58] Mein Kampf was translated into various Indian languages such as Hindi, Gujarati, Malayalam, Tamil and Bengali.[59]

Israel

An extract of Mein Kampf in Hebrew was kickoff published in 1992 past Akadamon with 400 copies.[threescore] So the complete translation of the volume in Hebrew was published by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1995. The translator was Dan Yaron, a Vienna-born retired instructor and Holocaust survivor.[61]

Latvia

On 5 May 1995 a translation of Mein Kampf released by a small-scale Latvian publishing house Vizītkarte began appearing in bookstores, provoking a reaction from Latvian authorities, who confiscated the approximately ii,000 copies that had made their fashion to the bookstores and charged director of the publishing house Pēteris Lauva with offences under anti-racism police.[62] Currently the publication of Mein Kampf is forbidden in Republic of latvia.[63] [ additional citation(s) needed ]

In Apr 2018 a number of Russian-language news sites (Baltnews, Zvezda, Sputnik, Komsomolskaya Pravda and Komprava among others) reported that Adolf Hitler had allegedly become more pop in Latvia than Harry Potter, referring to a Latvian online book trading platform ibook.lv, where Mein Kampf had appeared at the No. 1 position in "The About Current Books in vii Days" list.[64] [65] [66]

In research done by Polygraph.info who called the claim "false", ibook.lv was only the 878th most popular website and 149th most popular shopping site in Latvia at the fourth dimension, according to Alexa Internet. In improver to that, the website simply had 4 copies on auction past private users and no users wishing to buy the volume.[65] Owner of ibook.lv pointed out that the volume listing is not based on bodily deals, just rather page views, of which lxx% in the example of Mein Kampf had come up from anonymous and unregistered users she believed could be imitation users.[66] Ambassador of Latvia to the Russian Federation Māris Riekstiņš responded to the story by tweeting "everyone, who wishes to know what books are actually bought and read in Republic of latvia, are advised to address the largest book stores @JanisRoze; @valtersunrapa; @zvaigzneabc".[64] The BBC also acknowledged the story was false news, calculation that in the last iii years Mein Kampf had been requested for borrowing for only 139 times beyond all libraries in Republic of latvia, in comparing with around 25,000 requests for books about Harry Potter.[66]

Netherlands

In the netherlands Mein Kampf was not available for sale for years following World War Two.[67] [68] Sale has been prohibited since a courtroom ruling in the 1980s. In September 2018, nevertheless, Dutch publisher Prometheus officially released an academic edition of the 2016 German translation with comprehensive introductions and annotations by Dutch historians.[69] Information technology marks the get-go time the book is widely bachelor to the general public in the Netherlands since World War Two.

Romania

On xx April 1993, under the sponsorship of the vice-president of the Democratic Agrestal Party of Romania, Sibiu-based Pacific publishers began issuing a Romanian edition of Mein Kampf. The local authorities promptly banned the sale and confiscated the copies, citing Article 166 of the Penal Code. Nevertheless, the ban was overturned on entreatment by the Prosecutor General on 27 May 1993. Chief Rabbi Moses Rosen protested, and on 10 July 1993 President Ion Iliescu asked the Prosecutor General in writing to reinstate the ban of further press and take the book withdrawn from the market. On 8 November 1993, the Prosecutor General rebuffed Iliescu, stating that the publication of the volume was an act of spreading data, not conducting fascist propaganda. Although Iliescu deplored this answer "in strictly judicial terms", this was the stop of the thing.[70] [71]

Russian federation

In the Soviet Wedlock, the publication "Mein Kampf" appeared ane of the start in 1933, translated by Grigory Zinoviev.[72] In the Russian Federation, Mein Kampf has been published at to the lowest degree three times since 1992; the Russian text is besides bachelor on websites. In 2006 the Public Chamber of Russia proposed banning the book. In 2009 St. Petersburg's branch of the Russian Ministry building of Internal Affairs requested to remove an annotated and hyper-linked Russian translation of the book from a historiography website.[73] [74] [75] On 13 April 2010, it was announced that Mein Kampf is outlawed on grounds of extremism promotion.[76]

Sweden

Mein Kampf has been reprinted several times since 1945; in 1970, 1992, 2002 and 2010. In 1992 the Government of Bavaria tried to cease the publication of the book, and the example went to the Supreme Court of Sweden which ruled in favour of the publisher, stating that the volume is protected past copyright, but that the copyright holder is unidentified (and not the Country of Bavaria) and that the original Swedish publisher from 1934 had gone out of business concern. It therefore refused the Government of Bavaria'south claim.[77] The only translation changes came in the 1970 edition, but they were merely linguistic, based on a new Swedish standard.[ citation needed ]

Turkey

Mein Kampf (Turkish: Kavgam) was widely available and growing in popularity in Turkey, even to the indicate where it became a bestseller, selling upwardly to 100,000 copies in just two months in 2005. Analysts and commentators believe the popularity of the book to be related to a ascent in nationalism and anti-U.S. sentiment. İvo Molinas of Şalom stated this was a issue of "what is happening in the Center East, the Israeli-Palestinian problem and the state of war in Iraq."[78] Doğu Ergil, a political scientist at Ankara University, said both far-right ultranationalists and extremist Islamists had found common ground – "not on a common agenda for the futurity, but on their anxieties, fears and hate".[79]

United States

In the United States, Mein Kampf can be constitute at many community libraries and can be bought, sold and traded in bookshops.[80] The U.Southward. authorities seized the copyright in September 1942[81] during the Second Globe War under the Trading with the Enemy Act and in 1979, Houghton Mifflin, the U.Due south. publisher of the book, bought the rights from the authorities pursuant to 28 CFR 0.47. More than 15,000 copies are sold a year.[lxxx] In 2016, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt reported that it was having difficulty finding a charity that would accept profits from the sales of its version of Mein Kampf , which it had promised to donate.[82]

Online availability

In 1999, the Simon Wiesenthal Heart documented that the book was bachelor in Germany via major online booksellers such as Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Later a public outcry, both companies agreed to end those sales to addresses in Deutschland.[83] In March 2020 Amazon banned sales of new and 2nd-hand copies of Mein Kampf , and several other Nazi publications, on its platform.[84] The book remains available on Barnes and Noble'due south website.[85] It is likewise bachelor in diverse languages, including German language, at the Internet Archive.[86] I of the first complete English translations was published by James Vincent Murphy in 1939.[87] The Murphy translation of the volume is freely available on Project Gutenberg Australia.[88]

Sequel

Later on the party'southward poor showing in the 1928 elections, Hitler believed that the reason for his loss was the public's misunderstanding of his ideas. He so retired to Munich to dictate a sequel to Mein Kampf to expand on its ideas, with more focus on strange policy.

Only two copies of the 200-folio manuscript were originally made, and only ane of these was ever made public. The document was neither edited nor published during the Nazi era and remains known every bit Zweites Buch , or "2nd Book". To go along the document strictly hush-hush, in 1935 Hitler ordered that it be placed in a safe in an air raid shelter. Information technology remained there until being discovered by an American officeholder in 1945.

The authenticity of the document found in 1945 has been verified by Josef Berg, a onetime employee of the Nazi publishing house Eher Verlag, and Telford Taylor, a former brigadier general of the United States Army Reserve and Chief Counsel at the Nuremberg state of war-crimes trials.

In 1958, the Zweites Buch was found in the archives of the U.s. by American historian Gerhard Weinberg. Unable to detect an American publisher, Weinberg turned to his mentor – Hans Rothfels at the Institute of Gimmicky History in Munich, and his associate Martin Broszat – who published Zweites Buch in 1961. A pirated edition was published in English language in New York in 1962. The first administrative English edition was not published until 2003 (Hitler's Second Book: The Unpublished Sequel to Mein Kampf, ISBN 1-929631-16-2).

Meet too

- Berlin Without Jews, a dystopian satirical novel about German antisemitism, published in the aforementioned year as Mein Kampf

- Generalplan Ost, Hitler's "new order of ethnographical relations"

- Ich Kämpfe

- Gustave Le Bon, a main influence of this book and crowd psychology

- Listing of books banned by governments

- LTI – Lingua Tertii Imperii

- Mein Kampf in Arabic

- The Myth of the Twentieth Century

- Ukrainian military doctrine

References

Notes

- ^ Mein Kampf ("My Struggle"), Adolf Hitler (originally 1925–1926), Reissue edition (15 September 1998), Publisher: Mariner Books, Language: English, paperback, 720 pages, ISBN 978-1495333347

- ^ Shirer 1960, p. 85.

- ^ Robert Yard.L. Waite, The Psychopathic God: Adolf Hitler, Basic Books, 1977, pp. 237–243

- ^ Heinz, Heinz (1934). Frg'southward Hitler. Hurst & Blackett. p. 191.

- ^ Payne, Robert (1973). The Life and Death of Adolf Hitler. Popular Library. p. 203.

- ^ Shirer 1960, pp. eighty–81.

- ^ Bullock 1999, p. 121.

- ^ Richard Cohen. "Judge Who's on the Backlist". The New York Times. 28 June 1998. Retrieved 24 April 2008.

- ^ "Mein Kampf – The Text, its Themes and Hitler's Vision", History Today

- ^ "Mein Kampf". Internet Archive. 1941.

- ^ Browning, Christopher R. (2003). Initiating the Final Solution: The Fateful Months of September–Oct 1941. Washington, D.C.: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Centre for Advanced Holocaust Studies. p. 12. OCLC 53343660.

- ^ Graves, Philip (1921). The truth about 'The Protocols': a literary forgery (pamphlet) (articles drove). The Times of London. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013.

- ^ Hitler, Adolf. "XI: Nation and Race". Mein Kampf. Vol. I. pp. 307–308.

- ^ Nora Levin, The Holocaust: The Destruction of European Jewry 1933–1945

- ^ Ian Kershaw, Hitler 1889–1936 Hubris (1999), p. 258

- ^ Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, Book One – A Reckoning, Chapter XII: The First Period of Evolution of the National Socialist German Workers' Party

- ^ Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, Volume Ii – A Reckoning, Chapter Xv: The Right of Emergency Defense, p. 984, quoted in Yahlil, Leni (1991). "2. Hitler Implements Twentieth-Century Anti-Semitism". The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945. Oxford University Press. p. 51. ISBN978-0-nineteen-504523-ix. OCLC 20169748. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ A. Hitler. Mein Kampf (Munich: Franz Eher Nachfolger, 1930), p. 478

- ^ "Hitler's expansionist aims > Professor Sir Ian Kershaw > WW2History.com". ww2history.com.

- ^ Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, Eastern Orientation or Eastern policy

- ^ Joachim C. Fest (2013). Hitler. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 216. ISBN978-0-544-19554-seven.

- ^ a b c d "Mythos Ladenhüter" Spiegel Online

- ^ a b "Hitler dodged taxes, proficient finds" BBC News

- ^ Timothy W. Ryback (6 July 2010). Hitler's Private Library: The Books that Shaped his Life. Random Business firm. pp. 92–93. ISBN978-1-4090-7578-3.

- ^ a b "High demand for reprint of Hitler'southward Mein Kampf takes publisher past surprise". The Guardian. 8 January 2016.

- ^ "Mein Kampf work by Hitler". Encyclopædia Britannica. Concluding updated 19 Feb 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2015 from http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/373362/Mein-Kampf

- ^ Smith, Denis Mack. 1983. Mussolini: A Biography. New York: Vintage Books. p. 172. London: Paladin, p. 200

- ^ Uregina.ca Archived 25 Nov 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gunther, John (1940). Inside Europe. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 31.

- ^ Orwell, George. "Mein Kampf" review, reprinted in The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, Vol 2., Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus, eds., Harourt Brace Jovanovich 1968

- ^ Francis Stuart Campbell, pen proper noun of Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn (1943), Menace of the Herd, or, Procrustes at Large, Milwaukee, WI: The Bruce Publishing Company

- ^ Kuehnelt-Leddihn, p. 159

- ^ Kuehnelt-Leddihn, p. 201

- ^ Kuehnelt-Leddihn, pp. 202–203

- ^ Winston Churchill: The Second Earth War. Volume 1, Houghton Mifflin Books 1986, South. 50. "Here was the new Koran of faith and state of war: turgid, verbose, shapeless, but significant with its message."

- ^ Steiner, George (1991). Martin Heidegger. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. seven–viii. ISBN0-226-77232-2.

- ^ a b Bredeen, Aurelien (June 2, 2021) "Hitler's 'Mein Kampf' Gets New French Edition, With Each Lie Annotated" The New York Times

- ^ Schlamm, William S. (October 17, 1943) "German All-time Seller; MEIN KAMPF. By Adolf Hitler. Translated by Ralph Manheim. 694 pp. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. $iii.50." The New York Times

- ^ "'Mein Kampf' to see its first post-WWII publication in Deutschland". The Independent. London. 6 February 2010. Archived from the original on 12 February 2010.

- ^ a b Juergen Baetz (5 February 2010). "Historians Hope to Publish 'Mein Kampf' in Germany". The Seattle Times.

- ^ Kulish, Nicholas (4 Feb 2010). "Rebuffing Scholars, Frg Vows to Keep Hitler Out of Print". The New York Times.

- ^ "Bavaria abandons plans for new edition of Mein Kampf". BBC News. 12 December 2013.

- ^ Alison Smale (1 December 2015). "Scholars Unveil New Edition of Hitler's 'Mein Kampf'". The New York Times.

- ^ Vanessa Thorpe (26 December 2015). "British Jews give wary approval to the return of Hitler's Mein Kampf". The Guardian.

- ^ Eddy, Melissa (eight Jan 2016). "'Mein Kampf,' Hitler'due south Manifesto, Returns to German Shelves". The New York Times . Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ "Copyright of Adolf Hitler'south Mein Kampf expires". BBC News. Jan 2016.

- ^ "Mein Kampf hits stores in tense Deutschland". BBC News. 8 January 2016.

- ^ "The annotated version of Hitler'south 'Mein Kampf' is a striking in Germany". Business Insider.

- ^ "HOUGHTON-MIFFLIN, BEWARE!". The Sentinel. 14 September 1933.

- ^ "Hitler Aberration". The Sentinel. 8 June 1939.

- ^ § 64 Allgemeines, German language Copyright Law. The copyright has been relinquished for the Dutch and Swedish editions and some English ones (though not in the U.S., see below).

- ^ Judgement of 25 July 1979 – iii StR 182/79 (Southward); BGHSt 29, 73 ff.

- ^ "Jewish Leader Urges Book Ban End", Dateline World Jewry, World Jewish Congress, July/August 2008.

- ^ Bleustein-Blanchet, Marcel (1990). Les mots de ma vie [The words of my life] (in French). Paris: Robert Laffont. p. 271. ISBN2221067959. .

- ^ a b c d Braganca, Manu (10 June 2016). "La curieuse histoire de Mein Kampf en version française" [The curious history of Mein Kampf in the french version]. Le Point (in French). Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ Barnes, James J.; Barnes, Patience P. (2008). Hitler's Mein Kampf in Great britain and America: A Publishing History 1930–39. U.k.: Cambridge University Press. p. 271. ISBN978-0521072670. .

- ^ "Archiv – 33/2013 – Dschungel – Über die Wahrnehmung von Faschismus und Nationalsozialismus in Indien". Jungle-world.com.

- ^ Gupta, Suman (17 Nov 2012). "On the Indian Readers of Hitler's Mein Kampf" (PDF). Economic & Political Weekly. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 7 Feb 2021.

- ^ Noman, Natasha (12 June 2015). "The Foreign History of How Hitler's 'Mein Kampf' Became a Bestseller in India". Mic . Retrieved vii Feb 2021.

- ^ "Israeli Publisher Issues Parts Of 'Mein Kampf' in Hebrew". The New York Times. 5 August 1992.

- ^ "Hebrew Translation Of Hitler Book To Be Printed". The Spokesman-Review. sixteen Feb 1995. Archived from the original on 7 Feb 2021.

- ^ "Latvia Calls Halt to Sale of 'Mein Kampf'". Los Angeles Times. 21 May 1995. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen (18 June 2001). "Clemency returns £250,000 royalties for Hitler's credo". The Guardian . Retrieved nine October 2019.

Portugal, Sweden, Norway, Latvia, Switzerland and Hungary have also all forbidden publication.

- ^ a b Sprūde, Viesturs. "Fake News: In Republic of latvia Hitler'due south "Mein Kampf" is more than popular than Harry Potter". Museum of the Occupation of Latvia. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Sputnik and Zvezda Falsely Claim Hitler'due south Mein Kampf is more popular than Harry Potter in Latvia". Polygraph.info. 13 April 2018. Retrieved 9 Oct 2019.

- ^ a b c "Do Latvians actually read more Hitler than Harry Potter?". BBC News. ix October 2019. Retrieved ix Oct 2019.

- ^ "Shop possessor cleared of spreading hatred for selling Mein Kampf – DutchNews.nl". fourteen February 2017.

- ^ "metronieuws.nl cookie consent". tmgonlinemedia.nl.

- ^ "De wetenschappelijke editie van Mein Kampf – Uitgeverij Prometheus". Uitgeverij Prometheus (in Dutch). 23 August 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ Yoram Dinstein, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, i iun. 1996, Israel Yearbook on Human Rights: 1995, pp. 414-415

- ^ Solomon, Daniela (14 December 2015). "Cum a fost tipărit și ars la Sibiu volumul 'Mein Kampf' al lui Hitler". Turnul Sfatului. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Alexander Watlin. "Mein Kampf". What to do? Gefter (December 24, 2014).

- ^ "A well-known historiography web site shut down over publishing Hitler's book", Newsru.com, 8 July 2009.

- ^ "Моя борьба". 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ^ Adolf Hitler, annotated and hyper-linked ed. past Vyacheslav Rumyantsev, archived from the original 12 February 2008; an abridged version remained intact.

- ^ "Radio Netherlands Worldwide". Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ "Hägglunds förlag". Hagglundsforlag.se. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012.

- ^ Smith, Helena (29 March 2005). "Mein Kampf sales soar in Turkey". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Hitler volume bestseller in Turkey". BBC News. eighteen March 2005.

- ^ a b Pascal, Julia (25 June 2001). "Unbanning Hitler". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ "The Milwaukee Journal" – via Google News Annal Search. [ dead link ]

- ^ "Boston publisher grapples with 'Mein Kampf' profits" The Boston Globe Retrieved iii May 2016.

- ^ Beyette, Beverly (5 January 2000). "Is hate for sale?". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Waterson, Jim (xvi March 2020). "Amazon bans sale of most editions of Adolf Hitler'southward Mein Kampf". The Guardian.

- ^ "Mein Kampf". Barnes & Noble. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ "Internet Annal Search: Mein Kampf". archive.org.

- ^ Spud, John (14 January 2015). "Why did my granddaddy translate Mein Kampf?". BBC News. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ^ "Mein Kampf – Project Gutenberg Australia".

Bibliography

- Bullock, Alan (1999) [1952]. Hitler: A Study in Tyranny. New York: Konecky & Konecky. ISBN978-1-56852-036-0.

- Shirer, William L. (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Further reading

-

- Hitler

- Hitler, A. (1925). Mein Kampf, Ring ane, Verlag Franz Eher Nachfahren, München. (Volume ane, publishing visitor Fritz Eher and descendants, Munich).

- Hitler, A. (1927). Mein Kampf, Band 2, Verlag Franz Eher Nachfahren, München. (Volume ii, later on 1930 both volumes were but published in 1 book).

- Hitler, A. (1935). Zweites Buch (trans.) Hitler's Second Book: The Unpublished Sequel to Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler. Enigma Books. ISBN 978-ane-929631-61-2.

- Hitler, A. (1945). My Political Testament. Wikisource Version.

- Hitler, A. (1945). My Private Will and Testament. Wikisource Version.

- Hitler, A., et al. (1971). Unmasked: two confidential interviews with Hitler in 1931. Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-1642-0.

- Hitler, A., et al. (1974). Hitler'due south Letters and Notes. Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-012832-1.

- Hitler, A., et al. (2008). Hitler's Table Talk. Enigma Books. ISBN 978-one-929631-66-7.

- A. Hitler. Mein Kampf, Munich: Franz Eher Nachfolger, 1930

- A. Hitler, Außenpolitische Standortbestimmung nach der Reichtagswahl Juni–Juli 1928 (1929; first published as Hitlers Zweites Buch, 1961), in Hitler: Reden, Schriften, Anordnungen, Februar 1925 bis Januar 1933, Vol IIA, with an introduction by G. L. Weinberg; M. Fifty. Weinberg, C. Hartmann and Chiliad. A. Lankheit, eds (Munich: M. G. Saur, 1995)

- Christopher Browning, Initiating the Final Solution: The Fateful Months of September–Oct 1941, Miles Lerman Center for the Written report of Jewish Resistance, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (Washington, D.C.: USHMM, 2003).

- Gunnar Heinsohn, "What Makes the Holocaust a Uniquely Unique Genocide", Journal of Genocide Research, vol. two, no. three (2000): 411–430.

- Eberhard Jäckel/Ellen Latzin, Mein Kampf (Adolf Hitler, 1925/26), published eleven May 2006, English version published 3 March 2020; in: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

-

- Others

- Barnes, James J.; Barnes, Patience P. (1980). Hitler Mein Kampf in United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland and America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing.

- Jäckel, Eberhard (1972). Hitler'southward Weltanschauung: A Blueprint For Ability. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN0-8195-4042-0.

- Hauner, Milan (1978). "Did Hitler Want World Domination?". Journal of Contemporary History. Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 13, No. 1. 13 (1): 15–32. doi:10.1177/002200947801300102. JSTOR 260090. S2CID 154865385.

- Hillgruber, Andreas (1981). Frg and the Two World Wars. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Printing. ISBN0-674-35321-eight.

- Littauer-Apt, Rudolf 1000. (1939–1940). "The Copyright in Hitler'south 'Mein Kampf'". Copyright. v: 57 et seq.

- Michaelis, Meir (1972). "Earth Power Status or World Dominion? A Survey of the Literature on Hitler'due south 'Plan of World Dominion' (1937–1970)". The Historical Journal. 15 (2): 331–360. doi:ten.1017/s0018246x00002624. JSTOR 2638127.

- Rich, Norman (1973). Hitler'due south War Aims. New York: Norton. ISBN0-393-05454-3.

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh (1960). "Hitlers Kriegsziele". Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. 8: 121–133. ISSN 0042-5702.

- Zusak, Markus (2006). The Book Thief. New York: Knopf. ISBN0-375-83100-two.

External links

- A review of Mein Kampf by George Orwell, first published in March 1940

- Hitler's Mein Kampf Seen As Self-Help Guide For Republic of india's Concern Students The Huffington Post, 22 April 2009

- Hitler volume bestseller in Turkey, BBC News, xviii March 2005

- Protest at Czech Mein Kampf, BBC News, 5 June 2000

- Mein Kampf a hit on Dhaka streets, BBC News, 27 November 2009

- Hitler's book stirs anger in Azerbaijan, BBC News, 10 December 2004

- "Mein Kampf:" - Adolf Hitler's volume Archived 19 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, a Deutsche Welle telly documentary covering the history of the book through gimmicky media and interviews with experts and German citizens, narrated in English, 15 August 2019

Online versions of Mein Kampf

-

- German

- 1936 edition (172.-173. press) in German Fraktur script (71.4 Mb)

- 1943 edition (three.8 MB)

- German version as an audiobook, human-read (27h 17m, 741 Mb)

-

- English

- 1940 Mein Kampf: Operation Sea Lion Edition at archive.org

- Murphy translation at Gutenberg

- Murphy translation at greatwar.nl (pdf, txt)

- Complete Dugdale abridgment at archive.org

- 1939 Reynal and Hitchcock translation at annal.org.

DOWNLOAD HERE

Posted by: blackwellteaks2002.blogspot.com

0 Comments